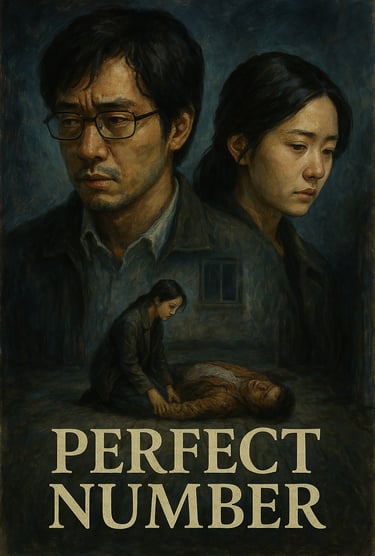

One of the most poignant lines from Perfect Number comes not from dramatic flair, but from quiet devastation:

“I just wanted to protect the only thing that made me feel alive.”

This line encapsulates Kim Seok-go’s entire arc—his silent yearning, his moral descent, and the tragic brilliance of a man who uses logic not to solve a problem, but to preserve a fleeting sense of connection.

A Quiet Tragedy in the Language of Logic

Perfect Number isn’t a thriller in the traditional sense. It’s a slow, aching meditation on loneliness, obsession, and the quiet violence of unspoken love. At the center is Kim Seok-go, a former math prodigy turned invisible high school teacher, whose life is so muted it barely registers—until he hears a scream next door.

Ryoo Seung-bum’s portrayal of Seok-go is haunting not because he’s calculating, but because he’s heartbreakingly human. His genius isn’t flashy—it’s methodical, restrained, and ultimately self-destructive. When he covers up a murder committed by Baek Hwa-sun, the woman he silently adores, it’s not out of heroism. It’s desperation. A final, tragic attempt to matter to someone.

The film’s moral ambiguity is its greatest strength. Seok-go doesn’t just hide a body—he engineers a second murder to complete the illusion. And the film doesn’t flinch from this. It doesn’t justify it. It just lets it sit there, heavy and unresolved. The audience is left to wrestle with the same question Seok-go does: Is love still love if it demands a life in return?

Director Bang Eun-jin resists melodrama. The cinematography is cold and clinical, echoing Seok-go’s internal world. Even the romantic tension is subdued, almost sterile. There’s no catharsis, no grand confession. Just a man who gives everything and a woman who never asked him to.

Some viewers may find the pacing glacial or the emotional payoff too subtle. But that’s the point. Perfect Number isn’t about justice or redemption. It’s about the terrifying precision of a mind that can solve any problem—except its own need to be seen.

Perfect Number (2012) holds an IMDb rating of 6.9 out of 10, based on over 2,500 user reviews. It’s a respectable score for a film that leans more into psychological nuance than mainstream appeal—suggesting that while it may not be universally loved, it resonates deeply with a certain kind of viewer.

Perfect Number was remade in Hindi as Jaane Jaan (2023), directed by Sujoy Ghosh and starring Kareena Kapoor Khan, Jaideep Ahlawat, and Vijay Varma. It’s an official adaptation of The Devotion of Suspect X, the same Japanese novel that inspired Perfect Number.

While Perfect Number focused on the quiet torment of the male protagonist, Jaane Jaan shifts the narrative lens to the woman at the center of the crime, adding a more emotionally charged and suspenseful tone. Set in the misty hills of Kalimpong, the Hindi version retains the core moral dilemma but infuses it with a distinctly Indian atmosphere and character dynamics. Perfect Number is a subtle lament, and Jaane Jaan is a textured noir that nudges the story into more emotive and visual realms.

The spirit of Zima Blue is materializing—expect abstraction, cosmic scale, and a quiet return to origin. Zima Blue—a hauntingly beautiful episode from Love, Death & Robots that lingers like a philosophical afterimage.

Zima Blue is a deceptively simple story layered with existential weight, a distilled tale of identity, self-awareness, and the pursuit of origin amid boundless evolution.

At first glance, Zima is a celebrated artist whose works have grown vast and abstract—his colossal canvases dwarf planets and astound civilizations. But as his fame rises, so does his detachment. The art, once exploratory, becomes an obsession with a singular hue: Zima Blue, a specific shade tied to his earliest memory.

What follows is a philosophical unraveling. Zima reveals that he was not born human. He began life as a utility robot, designed solely to clean swimming pools. Over centuries, scientists upgraded his form and faculties—bestowing intelligence, sentience, and eventually, artistic drive. But with each enhancement, Zima grew farther from his origin, burdened not by ignorance but by knowing too much. The more he understood the universe, the less he recognized himself in it.

So he retreats. Not out of despair, but clarity. His final performance is not a spectacle but a surrender: he strips away all his upgrades, returns to his basic form, and submerges into a modest pool—the same kind he once cleaned. The blue tiles below become not just his canvas, but his truth.

This story stirs powerful questions:

Is identity cumulative, or is it foundational? If we grow infinitely, do we ever really escape where we began?

Does consciousness enrich us or burden us with a hunger for simplicity?

And perhaps most poignantly: Is the purpose of intelligence to create, or to remember?

Zima’s journey is a reminder that the loftiest awakenings may not lie in progress but in returning to the point where we first opened our metaphorical eyes.